Tyrannical regimes are infamous for the suppression of civil and human rights. Dictatorships scrupulously control the populace and keep a tight grip on power through coercion and the removal of liberty, mainly the ability of its people to opine or express disagreement with the government or its leaders. Freedom of thought and the freedom to ruminate, cogitate, and form one’s own ideas are the fundamental platforms of a democracy and, therefore, feared by despotic governments.

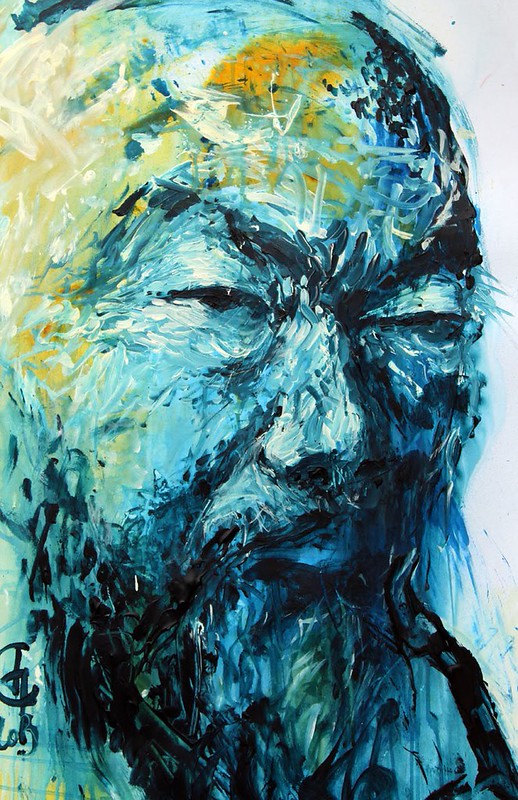

Art, in all its forms, is a vehicle of communication that not only gives voice to the artist but is also often a call to arms or a cry for help for society.

In a world of text messaging, flash mobs, and social networks, words and images sent aloft can reach millions of people in seconds and — as seen with the “Arab Spring” — can change the world. Repressive rulers know this and do their best to shut it down. China is notorious for limiting Internet access and, in some cases, forbids its people from sending messages; most notable amongst them is world-renowned artist and activist, Ai Weiwei.

Arrested last year, Weiwei was whisked away by authorities and held for 81 days without his whereabouts or “crime” disclosed to his family or the public. Eventually released, placed under house arrest, and finally accused of tax evasion (a purported fabrication), he was fined $2.4 million. The Chinese government rejected Weiwei’s appeal in July 2012, and it was reported that police prevented him from attending the hearing. Although Weiwei’s art isn’t always politically motivated and much of it is based on social ills, it was his words that irked the government the most.

The outspoken Weiwei embraced the social network, which allowed him to reach around the globe with his message of expressing his anger at abuses of power. His detention followed a clampdown by the Chinese government meant to curtail a call by activists for an “Arab Spring” style protest. Those in power also sought to squelch the growing unrest in Tibet over China’s harsh policy.

Acknowledging his earliest attempts at blogging, Weiwei said, “My first blog post was one sentence, something like: ’To express yourself needs a reason, but expressing yourself is the reason.’” It doesn’t get any more basic than that.

In ancient Greece, one of the most artistic civilizations in history, Plato cautioned the state to control art for the good of society. “Otherwise,” he warned, “art threatens the stability of the state.”

Followers of Karl Marx were so sure of the influence art had on the masses that they, too, considered art an appropriate subject for state control. In one such incident from the Soviet Union in 1946, artist Nikolai Getman was imprisoned in a Siberian Gulag. His crime? He was with several fellow artists when one drew a caricature of Stalin. An informant told authorities, and the entire group was arrested for “anti-Soviet behavior.” As a result, Getman spent eight years in a forced labor camp.

In America, the intent of the First Amendment has been muddled over the past several decades. Obscenity laws have been established, in large part, because of special interest groups, and now encompass any art form that meets with their disapproval.

In 1988, photographer Andres Serrano received angry reproach for his photograph titled “Piss Christ,” which depicted a plastic crucifix floating in a jar of urine. Bombarded by church leaders and religious groups, many senators sent protests to the NEA, insisting that the agency cease underwriting “vulgar” art. Yet, it is unlikely the senators even saw Serrano’s work before caving to their special interest constituencies. Religious radicals in France took a hammer to the work and destroyed the photograph in 2011.

A fundamental element in any discussion of censorship is that, regardless of your point of view about Serrano’s concept, what is considered obscene by some is not so by others. Both points of view are valid, and each deserves the right to be voiced and not censured.

Another outcry occurred in 1989 over the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe, who had received NEA support for his work depicting naked children, homosexuality, and sadomasochism.

Later that same year, the Helms Amendment, drafted by Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), was adopted, thus giving the NEA the “freedom” to define obscenity and even stifle alternative artistic visions. To enforce the amendment, the NEA established an obscenity pledge, absurdly requiring artists to promise they would not use government money to create works of an obscene nature. Astonished by the legislative vagaries, many museum directors resigned in protest, and several well-known artists returned their NEA grants.

A few years later, the legislation was challenged in court, resulting in the NEA abolishing the obscenity pledge and replacing it with a “decency clause,” which required award recipients to ensure that their works met specific standards of decency.

Artists through the centuries have turned to artmaking in times of war, conflict, oppression, and trauma. From Francisco Goya’s horrific portrayal of the Disasters of War to South Africa’s William Kentridge’s probing imagery of his conflicted identity as a white man and artist during Apartheid, resistance art has been a way of showing opposition to power holders. The term resistance art was coined to define art opposing the Nazi party — the same gang of thugs who declared expressionistic and avant-garde art as decadent.

The Soviets confiscated impressionistic and contemporary artwork for the same reasons. Many countries today, like Iran, Burma, and Syria, continue the practice of outlawing particular artistic expression or anti-government imagery.

As unimaginable as it seems, North Korea has banned virtually all art forms. Dissident painter Song Byeok stated recently that there are no (independent) artists in North Korea. “There just can’t be. There cannot be,” he said. “When you block someone’s ears and eyes since they’re born, you don’t even think about doing something individualistic like that.”

Following his attempt to cross the Chinese border to find food, Song was imprisoned and tortured by the North Korean government. He eventually escaped the country and now uses his art to condemn the regime he was once forced to exalt through propaganda posters and murals.

While living in North Korea, Song never created anti-government artwork because, he says, “The independence of thought necessary to create unofficial art simply doesn’t exist in the state. The fact is that I would never even think about it. That is why I wouldn’t ever think about the risks.”

There is a glimmer of hope for artists who live in such an Orwellian world. The World Conference on Artistic Freedom of Expression will be held in Oslo in October. Artists who have received death threats, experienced imprisonment, abduction, or censorship because of their artistic work will be given a global voice at the conference. The website (http://artsfreedom.org) is the first of its kind and intends to set a new standard for documenting censorship of artistic freedom of expression.

For artists living and working in less oppressive nations, it is safer, if not easier, to create freely. It’s an advantage not to be taken for granted — one that should be cherished and appreciated by us all.

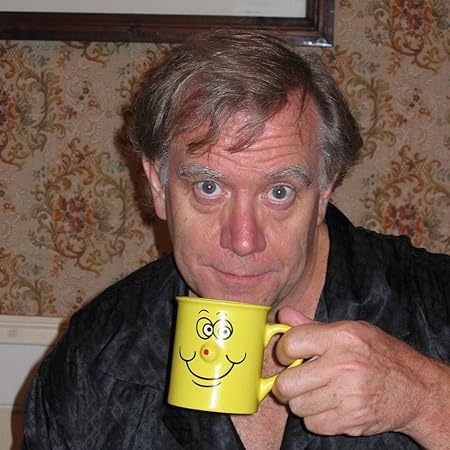

In Memoriam

Stew Mosberg

January 7, 2019

Arts Perspective honors the memory of our longtime contributor and colleague, Stew Mosberg — a gifted writer, editor, and arts advocate whose insight and passion helped shape the cultural voice of our region.

A freelance writer and former arts publisher, Stew brought a lifetime of experience to his work. He authored two books on design, taught at Parsons School of Design in New York, and wrote widely about the creative life in Southwest Colorado and beyond. His thoughtful storytelling and dedication to elevating the arts community left a lasting mark on readers and fellow writers alike.

Stew’s legacy continues to inspire those who value curiosity, creativity, and the written word.

Editor’s Note

Reading Stew Mosberg’s “Fear the Art” again, I couldn’t help but think of our current moment — and how history has a way of circling back. With today’s cuts to arts programs and the shifting priorities of those in power, Stew’s words feel more urgent than ever. His essay reminds us that art isn’t just decoration or diversion; it’s dialogue, courage, and the voice of a free people. Revisiting his piece now felt necessary — a reminder of why artistic expression matters, and how easily it can be silenced when we stop paying attention.