I figured out how to fly. I don’t mean something crazy like jumping off the roof with a towel safety pinned to my shoulders. I would soar through the air above the heads of teachers and kids. The slide was right next to the seesaw, making it perfect for creating the greatest stunt ever conceived by a fourth grader. I could see Ed Sullivan inviting me to repeat the feat on his Sunday night show. The audience would be hushed in anticipation. I would be dressed, not in a brown corduroy jumper and saddle shoes, but in a silver costume with gold flames down my arms.

For three and a half years, nobody had noticed me, no matter how many amazing things I’d done. I’d handled John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign at our school. I had made posters and speeches and asked for votes, with the result being his landslide election. I was the one who came up with the Secret Society of Letters after my aunt sent me a printing set that had letters and numbers and a little ink pad you could use to print your own newspaper. The fact was, I was tired of being ignored, which is why I had decided to attempt the trick.

My role model was the skinny man I saw at the circus. The stage had gone dark, and everyone wondered if the show was over. Then, suddenly, a spotlight appeared, illuminating a black iron cannon with a long fuse. We heard a drumroll, and the man entered the circle of light. His hair was slicked back to prevent drag. He climbed into the barrel. All we could see were his arms, pointed to the sky. Then a beautiful woman in a glittery, short red dress stepped forward and struck the biggest match I’ve ever seen. I didn’t breathe as fire crept down the fuse to the gunpowder that would blow the man to kingdom come. There was a moment when it looked like it had gone out. Still, after the slightest hushed delay, the tent was filled with the boom of an explosion, and the human bullet flew from the barrel into the sky, crashing into a net that was the only thing that prevented him from shooting through the roof and into space.

I closed my eyes, afraid he was dead, but he wasn’t. He flipped over the edge of the net a moment later with a big “Ta Dah!” and the crowd cheered. It was the most wonderful thing I’d ever seen. In school, when I was supposed to be turning fractions into decimals, I was drawing pictures of the stunt. When I was supposed to be memorizing “Casey at the Bat,” I sketched intricate plans that looked like aeronautical designs at an airplane manufacturing plant.

When I knew I was ready to show just what amazing things I could do, my friend Cindy seemed to be my most logical assistant. The only other choice would be Marlene, but she wasn’t that smart and probably wouldn’t understand the science involved.

When we finished our spelling test and everyone went to the back of the room to line up for a drink of water, I pulled Cindy aside.

“Hey! I was in line!”

“This is important. I need your help, and I don’t want anyone to know what’s up.”

“You’re going to get me in trouble again,” she hissed through her missing front teeth. Everyone else in our class had lost their front teeth in second grade, but not Cindy. She had waited. That was how she was with everything. She was late getting in on things.

“You aren’t going to get in trouble. I need you to help me with a trick.”

“What kinda trick?”

“I want you to climb up the slide and jump off onto the seesaw, which will be up because I will be standing on the other end.”

“Are you crazy?”

That was a good one, her accusing me of being out of my mind when I knew insanity ran in her family. It was the only reason I could come up with for why Cindy’s teenage sister would suddenly be pulled out of school, and why she didn’t come back until several months later, showing off a skinnier body. (Even I had noticed she’d been putting on weight around the middle.) When grown-ups talked about it, they whispered and then stopped talking altogether when a kid came around. I wasn’t stupid. I figured out what was going on. She’d been in the loony bin having electroshock therapy.

“You don’t have the hard part,” I explained.

“While I’m breaking my neck jumping off of a twelve-foot-high slide and you’re just standing on the teeter totter, how does that make yours the hard part?”

“Oh,” I said, putting my arm around her and walking to the window. We had a perfect view of the slide and the seesaw, now standing there alone without any kids around. “I will be flying.”

She looked at me and pulled away. “You’re nothing but a big show off. I don’t want to do it.”

“Let me just take you through the scenario.”

I explained every detail, even referring to my sketches. I could tell from the way she was looking at me that she was thinking the very same thing I was. It was so simple, it was elegant. I would stand at the end of the seesaw, which would be on the ground. Cindy would climb slowly and deliberately to the top of the slide, and with the whole playground watching, she would stun them. Instead of sliding to the bottom, she would stand on the top and leap to the side. As everyone gasped, she would land on the upper end of the teeter-totter. It would crash to the ground with enough force to launch me high into the air. After executing a perfect flip, I would land back on the seesaw, and Cindy and I would begin the traditional oh-so-boring style of up and down. No one would ever doubt the degree of courage it took to execute such a trick. Cindy looked at me, and then out at the slide. I could tell she was picturing the whole thing in her head.

“You should wear your pink tights,” I urged. “That would be a nice touch.”

She got back into the drinking fountain line.

“Well? Wahddya think?”

“No.”

“Come on! You’re a nobody in this room. Life is short, Cindy. We have to make our mark when we get the chance.”

“No.”

“Whaddya mean, no?”

“No.”

I hadn’t planned on this response. Cindy could never have come up with an idea like this on her own. Besides, I needed a partner. That’s when I turned around and saw Melvin Carter, the judge’s kid, staring at me. He had my plans in his hands.

“I’m gonna tell.”

He started to leave so I had to grab him by one of his scrawny little arms. “Oh no you’re not. You’re going to be in the show.”

There was a look of terror on his face interrupted by Cindy.

“Wait a minute! I thought I was going to be in the show.”

This was a totally unexpected but interesting turn of events.

“I don’t know, Cindy,” I said, looking at her with concern. “You got a little heavy over summer vacation. I’m thinking Melvin would look better in the role of my assistant.”

Melvin registered a sense of pride that lasted about half a second.

“Maybe I’m fatter now, but that would be good,” Cindy said.

“How do you figure?”

“Think about it. I’m jumping off the slide onto the seesaw. The point is to make you fly up into the air.”

“Yeah.”

“Well, look at Melvin. How would that look if you’re just standing there ready to fly and Melvin is too skinny to shoot you into the air?”

“You might have a point there. How much do you weigh, Melvin?”

Melvin was sweating and more than a little disturbed.

“You might be right,” I said. “I have an idea. I know Melvin will be disappointed, but how about you being the announcer, Melvin?”

“Announcer?”

“You know, like the ringmaster at the circus.”

“I don’t know …”

“There’s no chance you could get hurt. When Cindy and I are ready, you’ll take a bullhorn and call everyone’s attention to this side of the playground. When everyone gathers, you’ll introduce the act.”

“I wouldn’t know what to say.”

“And we don’t have a bullhorn,” Cindy interjected.

“Those are details,” I continued. “I think we all know what we’ve got to do. We’ll have a run-through at morning recess tomorrow and be ready for the performance right after lunch.”

I headed for my desk, leaving Melvin and Cindy staring at each other. “Oh, and don’t forget those pink tights,” I called back. “Not you, Melvin.”

The next morning, I got up and looked through my closet, searching for the perfect costume. Most everything was too ordinary. The only thing that I could do was the pink Easter dress. I’d worn it the April before, but Cindy wasn’t the only one who’d grown. It was a snug fit, but by holding my breath, I was able to force the buttons together. The gaps showed my tummy a little more than I would have liked, but I pulled on an old green sweater and took a quick spin in front of the mirror. I grabbed the crinoline cancan I’d had for the dance recital and shoved it into my book bag to put on later.

“What are you wearing?” My mother asked when I slid into my place at the table. She and Dad exchanged looks and my little sister giggled.

“I just think it’s a crying shame to wear a perfectly good dress one time and outgrow it before you ever put it on again,” I explained. “I’m just trying to show a little bit of common sense.”

My parents exchanged looks, and Mom put a pancake on my plate, which I buttered well and poured a half pitcher of syrup on. Every time I swallowed, I could feel the strain on the dress buttons, and one of them popped off when I leaned over to slip on the cowboy boots Uncle Bill had presented to me on his last visit.

It was hard to keep my mind on my arithmetic that morning, mostly because I was so excited, but also because the other kids were staring at me. We didn’t have morning recess because of a school assembly, so we didn’t get a practice run. I went over the whole thing in my mind instead. I knew that to get the best dramatic effect, I had to keep my arms tight at my sides until I had reached the top of my ascent into the sky. At that exact moment, I had to go into a perfect tuck and complete a double flip on the way down.

I’d tried to practice for real when we got a chance to jump on the trampoline in gym class, but there were thirty kids, one trampoline, and one gym teacher screaming about my time being up and letting someone else have a turn if all I was going to do was bounce around in a circle. She didn’t realize I was jumping in circles to build momentum and get enough height to try the flip. Still, it was enough to get the feel of it.

The time to act was nearing, but when Mrs. French, our teacher, announced that we needed to finish our papers so we could go to lunch, Melvin let out a kind of dying animal noise. He threw himself onto the floor and started crying. Nobody knew what was wrong with him, but he managed to communicate in sobbing, stumbling gasps that he wanted to go home. Mrs. French got him up and took him to the nurse’s office.

When she was gone I turned around and looked at Cindy. I couldn’t help noticing she hadn’t worn her pink tights. When Miss Andrews told us to line up to go to lunch, I fell into line next to Cindy.

“You’ll have to fill in for Melvin,” I told her.

“No talking in line,” Miss Andrews hissed.

“No.”

“It’ll be fine. You’ll be up on the slide. That’s really a better place to announce the trick anyway.”

“I said no. I’m not going to help you.”

“I’ll tell everyone where your sister was when she was gone.”

Her face drained of blood, and her bottom lip started to tremble. I didn’t expect that kind of response and was even more surprised at her words.

“How do you know where she was?” She was scared. “Please don’t tell anybody! I’ll do anything you say.”

We moved through the line with our green plastic cafeteria trays to get our sloppy joes and pear salad and sat down at one of the long tables. Cindy was crying, and I was confused.

“I’m sorry, Cindy. You don’t have to help me. And I won’t tell anyone where she went. Please don’t cry.”

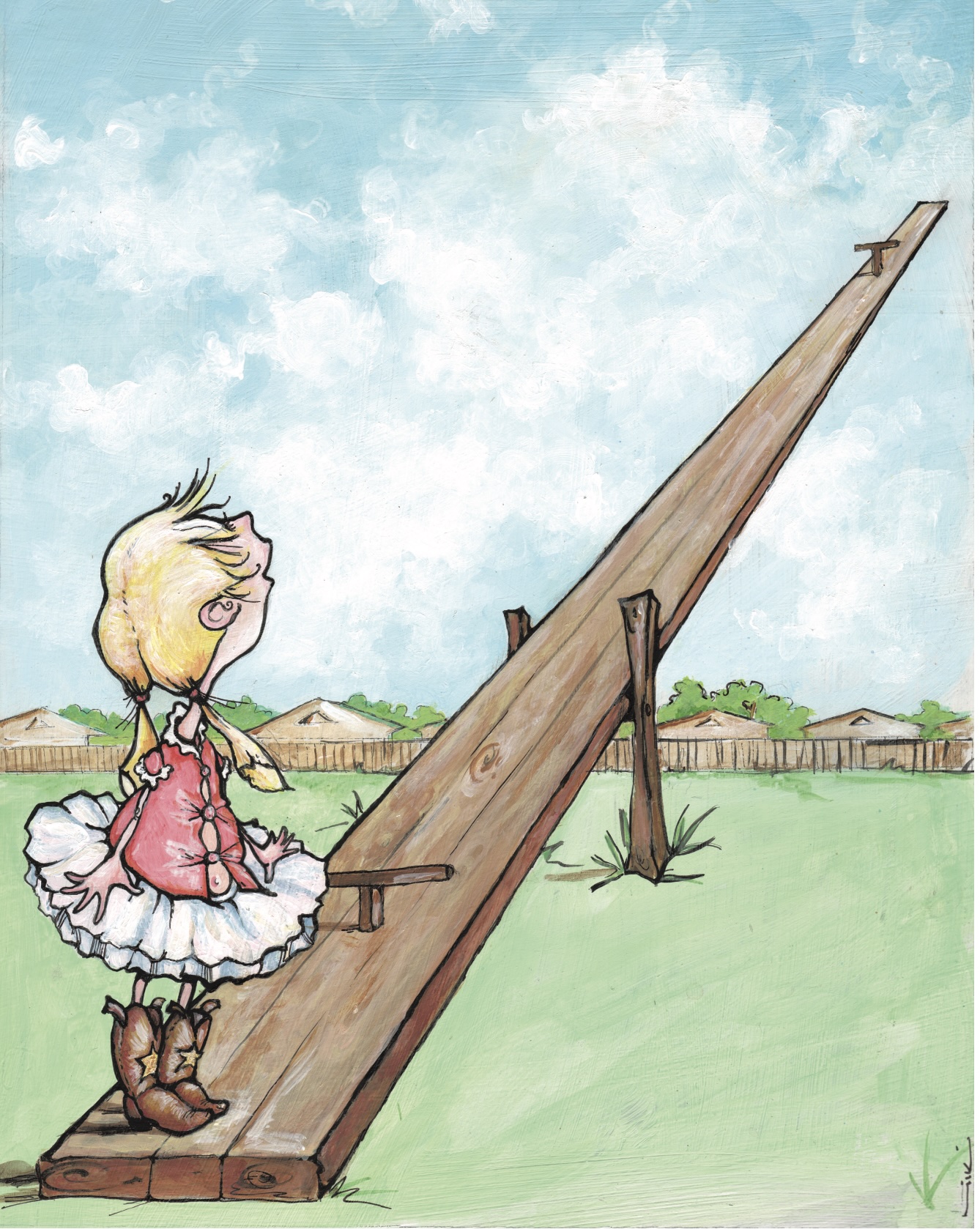

She looked up in relief, and we both began to eat. My heart was broken. I was dressed perfectly, and I knew what I was doing. I took a bite of sloppy joe and felt another one of my dress buttons pop off. When I wandered out to the playground, the slide and seesaw were empty. I stepped onto the end of the seesaw and bounced a little, getting my balance and thinking about the glory that might have been. I had on my cowboy boots, I’d removed my green sweater, and I’d put on my can-can under the pink Easter dress so it stood out at a ninety-degree angle. If I had impressed everyone with my flight into the stratosphere, maybe they wouldn’t think I was so strange. Perhaps I wouldn’t be picked last when we divided up for dodgeball teams.

And then I realized someone was climbing the ladder to the slide. It hadn’t dawned on me that Cindy would change her mind.

“You came!” I cried. But it wasn’t Cindy.

It was Arnold. He was at the top of the slide, looking down at me. Arnold was the biggest, meanest, scariest kid in school. Even though he was in fourth grade, he’d been held back so many times he should have been in junior high. He was looking at me with a strange kind of evil grin and laughed as he threw himself off the top of the slide. I didn’t have time to stop him. I didn’t have time to call all the other kids to watch. I didn’t have time to mentally review my performance, making sure I was standing up straight and ready to tuck and roll. He hit the seat, and I shot into the sky.