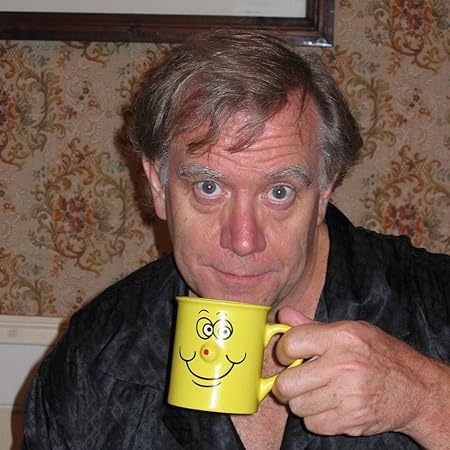

UCLA Professor Emeritus Lorenzo Sifuentes, recently turned 80, adjusted his glasses: his new black “computer” glasses. Although his habit for over 50 years had been to compose his poems in pencil on yellow legal pads, it was time for his habits to change. A month after his wife Margo’s death he sent his son Marcus to the Apple store on the Santa Monica Promenade, instructing him to bring home “a fine poet’s computer.” At this point in life, money was not an issue: “Just use my gold card,” he instructed.

Maybe the new machine would actually unlock Lorenzo and facilitate the writing of a few more sublime verses. An after-the-fact elegy for Margo perhaps? Since the first years of their 53 year marriage, Margo had been his transcriber, his typist, and ultimately his word processor. Five years ago she had coaxed Lorenzo to start typing his own emails: now it was time to catch up with the times and compose his poems on the computer. “Pencils are for old men,” Lorenzo mused, trying to believe it as he thought it.

Sifuentes typed in a few words just to feel the square metal keys submit to his fingers. They were the first words he had written in three months, and they came slowly.

Marcus had, of course, followed his father’s instructions with passive aggressive avidity, bringing home a vast horizontal monitor and an expensive brushed steel processor vastly more powerful than any writer needed. As the aging professor forced out his few, solemn words, he mused that they were like the survivors of a shipwreck, struggling in a silver ocean. He was thinking of the words on the screen, but then he realized he was also thinking of himself and his son.

Lorenzo Sifuentes had been born with a metaphorical mind, for better and for worse. It was the fount of his genius, and also something of a handicap.

Necessarily, genetically and fatefully, his late mother, his late wife and his sole living offspring were all practical and literal minded. Lorenzo had been surrounded all his life by people who were different than him, but who stood in awe of him and served him loyally.

Lorenzo’s father had died in a car accident when his son was 6 months old: perhaps the random genius that marked Professor Sifuentes had come through that genetic conduit, but he could only speculate. He learned early in life not to bring up the subject of “that drunk” in front of his mother. Nature, Lorenzo believed, had made him different, not nurture. His childhood had been unremarkable until his 8th grade writing teacher had called his mother in for a conference. “Lorenzo,” he said with the boy present, “has a special gift.” And, in truth, he did.

Everything came to Lorenzo early and easily. Marriage to his high school sweetheart, rave reviews, a plum teaching job: all of these things were effortlessly his by the age of 26. What talent he had. Lorenzo could effortlessly say and write things that could take your breath away. The years brought an embarrassment of accolades, and a living room wall plastered with honorary degrees and tributes.

The plan had always been that Lorenzo would be the first to die. Margo would be fine: the Westwood house alone was worth $2.2 million, the university pension was generous, and the mortgage had been paid off twenty years ago before. Publishers were still sending checks, and the book of essays on Lorca was going into its fifth printing.

Ever since he had turned 50 Lorenzo had gone through some kind of health crisis every ten years or so – the encephalitis that hit him in Rome in 1983 had just about done him in – and Margo’s family had the longevity gene. Her father had made it to 92, her mother to 96. Lorenzo had already given Margo and Lorenzo several very beautiful, very maudlin “When I am gone…” speeches after the pacemaker was installed in his mid-seventies.

Death however had its own agenda. It always does.

Between the fateful morning when Lorenzo had first noticed something was wrong – “Margo, you are yellow,” he had told her as she stepped out of the shower – and her death from two kinds of cancer, there were only 63 days to fight, plan, cry and hold each other under the covers. When Margo died, Sifuentes was shocked to find, after all the years of marriage, just how much he had loved her. Even more shocking was the realization of how much he had depended on her. His grief was profound, his helplessness pathetic.

Marcus was pathetic in a different way. Forty-eight, grey in the temples and overly tanned, his second marriage had staggered through its final stages as his mother fought cancer. When the funeral came his soon to be ex-wife Nora had done him a favor by being there at all. What a mess this divorce was going to be: Nora and Marcus had owned a restaurant together that Lorenzo had of course given them the money to open. A failed restaurant, a failed marriage, and the death of a mother who had oiled all the gears: Marcus had a lot to face.

After his mother’s burial went straight to a bar, picked up a woman, and poured out his misery to her. “My father is a great man,” he told her sarcastically, “and now I am going to be his maid.”

Still, things started out reasonably well. In the weeks after Margo’s funeral relatives, friends and former students brought casseroles and took out the trash. Marcus moved out of the house he had shared with Nora for 13 years, and rented a two bedroom apartment ten minutes from his father’s place. He bought a bunk bed so his two boys could spend weekends, stocked the kitchen with a few stealthily procured things from the restaurant, and then walked away. Having an apartment at all was a futile gesture. He knew that for a few months at least, his grieving father would need him day and night.

Marcus did not become his father’s maid. An actual maid was hired, and along with vacuuming, dusting the folk art and making the beds, she left behind very nice frozen very nice beef empenadas for the weekends. Marcus served his father as a sort of amanuensis, just as his mother had.

He took nearly all the phone calls: only the “chosen few” had the professor’s direct cellphone number. Marcus handled all the dealings with publishers, literary agents, editors, bankers, lawyers and doctors. The week after his mother’s death Marcus arranged to have his father’s pool drained and re-plastered. Yes, he felt grief, yes the divorce was weighing on him, yes his father was a grieving pain in the ass, yes he was sad too, but the pool needed work. Maintenance, tangible work, grounded him. Add to that, Marcus was now on Lorenzo’s payroll. At least his father trusted him – or didn’t care about money – so he wrote checks to himself: $7k per month.

“Marcus,” the forgetful professor asked his son one morning over coffee, “just how much am I paying you?”

“Not enough,” Marcus countered, “take your Levatol.”

Marcus was an only son, born after three miscarriages. He had been a handsome, appealing boy, and he was the subject of his father’s poems for several years. Still, Marcus couldn’t help noticing that after the age of ten his father’s approval became more muted, has affection more distracted. In time, it all curdled into mild disapproval. Teenage Marcus chose – in the professor’s opinion – the wrong school activities, the wrong friends, and especially the wrong girls. Margo played the intermediary, but his father’s opinions lingered in the air. Even when Marcus finally excelled in something – soccer – Lorenzo rarely attended his games, and had trouble covering up the fact that he would really rather be at home writing.

Marcus’ first wife had married him, he found out quickly, to try and gain access to Lorenzo. That was a disaster. In his second marriage, Lorenzo’s name often came up in arguments. “Your father patronizes you,” Nora would tell him. “That’s true,” Marcus would respond. “But please, let’s not bring my Dad into this.”

In essence, Lorenzo was in every aspect of Marcus’ life whether he was wanted there or not. It was the “great man” effect. Growing up, there had been literally dozens of moments when a well-meaning adult at a book-signing or cocktail party had leaned down to ask him “Young man, are you a poet too?” Lorenzo, when he overhead these things would gently intervene. “Well, he is quite a poet with a soccer ball…”

Although he did try, Lorenzo was not a good father to Marcus. He wasn’t a bad one either: mainly the father and son were mismatched. Friends of the family, who observed the situation noted that fathering was really the only thing Lorenzo didn’t effortlessly do well. Paradoxically, Lorenzo could be fatherly towards students, but Marcus somehow grew up in the chilly shadow side of Lorenzo’s otherwise nurturing spirit.

With his father now dependent on him, Marcus rose to the occasion. Visitors commented on how well the house was running, and Lorenzo and Marcus got along better than they had in years. They were united by grief, and it helped that there were so many good restaurants in the neighborhood. Marcus enjoyed driving his father’s silver BMW, and he learned to sit back and enjoy the public moments when he overheard whispers at the next table. “Isn’t that Lorenzo Sifuentes?” The whisperers were often women his age, and Marcus learned over time to relax and simply say “Won’t you join us?”

Spending more time with his father, Marcus began to realize that although Lorenzo would always effortlessly surpass him in nearly everything, maybe the old man’s style could be mimicked. When he was in public with his father, Marcus listened more carefully than before. He also began to re-read his father’s poetry, something he hadn’t done in years. He could see that it was great, but he was also struck by how disconnected it was from life’s realities.

By the summer after his wife’s death, the professor had become productive at the computer, and a new anthology of poems was slated for publication. Marcus made sure at the end of each work session that his father’s working files were saved and sorted, and that his publisher received the latest poems via email.

When the new book was almost complete, the professor’s health took a turn for the worse, and he became depressed. Marcus would coax his father through each day, drive him to the doctor’s and turn most visitors away. In the evenings fights broke out between the father and son. Lorenzo, ill and morbidly obsessed reminded Marcus of his shortcomings, and Marcus held his own. One evening, after a few beers, Marcus told his father the truth, in simple unvarnished language: “You were a good husband to Mom, but you never knew how to be a father to me.” Lorenzo cried and admitted that it was true.

“I have been very self-absorbed… and I had no father myself,” Lorenzo offered. “I didn’t realize how much you needed my approval.”

These things had needed to be said for years.

After that night, something changed. For the first time since his early childhood, Marcus began to feel genuinely appreciated and approved of by his father. Marcus, who had been knocking himself out to care for the ailing professor, realized that the approval was well deserved. From the day of his mother’s death forward, Marcus had made smart decisions, seen to his father’s needs, and shown competence in dealing with the people and situations that needed attention. Visitors had been noticing this too, and Lorenzo’s friends complimented Marcus on what he had accomplished.

“Because of you,” a visiting editor told him, “your father has been able to write again.”

While his father watched TV one evening, Marcus logged in to the computer to look over the day’s writing, and to organize the files that were accumulating. His father’s most recent poem “Columbine: The Virgin’s Sorrows” was nearly three pages long, and Marcus read it dispassionately. Almost unconsciously, Marcus went to the end of the poem and added a few lines himself. He had read enough of his father’s work to mimic the style.

Then, he went back through the poem and changed a few words. Just making these small changes felt liberating: it was like winning an argument that had gone on for years. Working on his father’s poem felt both wrong and wonderful. When the TV went off in the next room, Marcus deleted his changes and re-saved the file. At least, years later, when he went over and over what had happened, that is what he told himself he thought he had done.

Two weeks later, Lorenzo died, peacefully, in his sleep. He and Marcus had both been in great spirits the night before: Lorenzo felt that his illness was receding. They had eaten at Lorenzo’s favorite restaurant, shared a fine bottle of wine and laughed together. Anyone who saw them that evening would have assumed that the father and son were each other’s best friends, and would have envied their close relationship.

The memorial service, which Marcus organized precisely as his father requested, had some off moments, but none of them were Marcus’ fault. The turnout was large, but not as large as expected. Many of the other writers, professors, poets and critics in Lorenzo’s circle had passed away, and a few that had been expected didn’t show up. Doris Larkin, Lorenzo’s literary agent for over 30 years, later phoned to offer personal condolences and then mentioned that she “just couldn’t handle the traffic.”

Jim Reiser, a literary critic and a lifelong friend of Lorezno’s, muttered his eulogy into the microphone and those in the back of the university chapel missed half of what he said. After the service, a bulb in the LCD projector burned out halfway through the Powerpoint made up from snapshots culled from Lorenzo and Margo’s photo albums.

It took the LA Times a few days to run Lorenzo’s obituary, and the New York Times ran only a short piece, written by a travel writer who had never met Lorenzo. All of the obituaries seemed to be largely based on Lorenzo’s Wikipedia entry, and there were a few small factual errors. Marcus made sure to write letters to the editor the next day to offer corrections.

Marcus decided not to sell his father’s house: there would be more than enough money for him to pay the property taxes and upkeep and hang on to it. He had practically been living there anyways, so he gave up the apartment, and his sons came to stay for two weeks, the longest time they had spent together since his divorce from Nora had become final. Marcus felt genuine grief over the loss of his father, and he was also grateful that they had been able to resolve so much before the old man’s death. Marcus felt fortunate. He met a new woman, and something about the new relationship felt right.

When his father’s book came out – “Lorenzo Sifuentes: Final Poems, 2010” – Marcus checked the papers every morning expecting so see a review, but nothing appeared. Eventually, Doris Larkin e-mailed him a link to a review that had appeared in a new literary blog. It was a very short piece titled: “A Once Great Poet’s Surprising Last Verses.”

“Thirty years ago Lorenzo Sifuentes was considered one of America’s leading poets, but his reputation has been in decline. The publication of a small anthology of his final poems will likely reverse this trend. A poet once known for his obscure references and esoteric metaphors, just weeks before his own death of heart failure, Sifuentes apparently found himself confounded and challenged by the death of his wife Margo. Grief wrought a change in the poet’s approach.

In Sifuentes’ final poem, ‘Columbine: The Virgin’s Sorrows,’ there is a surprising, unexpected and revelatory shift in tone. Sifuentes’ language, normally elusive, becomes lapidary and precise. Shifting from metaphorical speech to direct reference Sifuentes momentarily becomes another writer entirely. The result feels like a complete rebirth for a poet whose best years had seemed to be far behind him. ‘Columbine’ will be remembered as Sifuentes’ greatest poem, and is likely to cause a re-examination of interest in the poet’s prior works.”

Marcus sat at the monitor, absolutely silent for minutes, maybe even an hour.

“Oh fucking mother of Jesus!” he finally muttered out loud.

Then, Marcus screamed, to an empty house: “Papa! Papa, where are you? I need you!”